Polish mining is a threat to drinking water

for thousands of Czech people.

This problem is affecting Czech families living near the Polish Turów coal mine, which is causing drought, noise, dust, and flash floods. And the situation is about to get worse. Thousands of people are at risk of losing their access to drinking water. Many wells are already completely empty, and the area is drying out.

Despite the objections of the Czech Republic, operation of the mine was extended. That means Poland has been mining illegally since May 2020, and will continue to do so for the next 24 years.

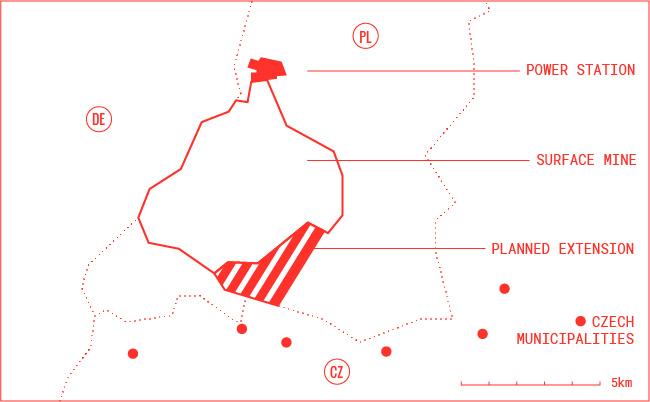

The mine will come as close as within 70 metres of the Czech border, threatening to dry out the whole area, including Czech wells.

The Turów brown coal mine and power station are located in south-western Poland near the Czech border. Mining has been carried out there since the 1960s. During its operation, the mine has caused substantial damage to the environment on Czech territory. The Jizera mountains were devastated by air pollution, and the groundwater level decreased by up to 60 m. The remaining water is still draining out towards the mine, and the increasing drought has also contributed to the worsening situation. However, instead of providing compensation for the historical damage, Poland has decided to prolong the mining. This is going ahead despite clear disagreement from neighbouring states.

Mining activity poses a threat to water sources, especially in the villages of Uhelná, Václavice, Oldřichov na Hranicích and Hrádek nad Nisou. The planned mining operations will cause a massive expansion of the area affected.

The residents will lose water.

In the village of Uhelná, located closest to the mine, the wells dried up many years ago. However, its inhabitants are connected to the water network. Those in the neighbouring village of Václavice aren’t so lucky, and have suffered from a long-term shortage of water. Other municipalities in the area could face a similar fate. Some families will have to get used to water delivered by fire trucks instead of tap water.

“Shall we run the dishwasher or the washing machine today?” That’s a question the Kronus family have to ask themselves frequently. The well is insufficient for their water needs. Even the water they carry from a stream to a barrel in their garden can’t be pumped into the washing machine, so they often run out of options at home, and have to do their laundry at the Unity of Brethren in Chrastava or at work.

People in Václavice have to get water from the stream.

“Even our family refuses to visit us.”

“They’re afraid of not being able to take a shower, since that has happened several times,” says Mr Kronus’s wife. Every evening they don’t know whether they will have enough water for themselves and their children the next day. The water level in their well is only a few centimetres high.

Your water network can deliver

1 litre of water in 5 seconds.

That is something Mr Kronus can only dream of. His village is not connected to the water mains and sometimes he can’t even fill a glass with water from his well.

Michal a Eva

Kopečtí

BOTH THE FAMILY AND THEIR HORSES

ARE SUFFERING

FROM THE WATER SHORTAGE.

Their story

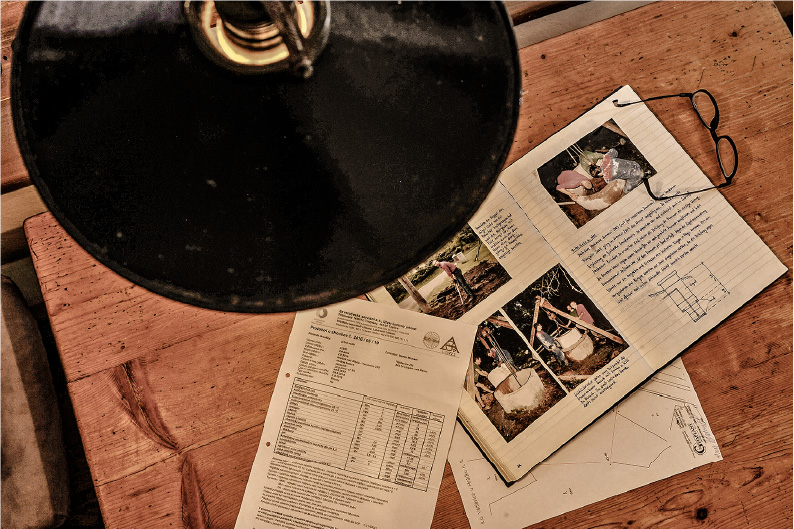

The mine has also denied water to horse breeders. For the past two years, their well has been so low they could barely provide water for their horses. Last year, they rented a 1,000-litre water tank from the town and it was filled by firemen. However, they won’t be able to rely on them in the future.

Last year they got their water from firemen. What about this year?

2 beers for a batch of laundry

Their options for drinking water for their kitchen or bathroom are either bottled water from a shop, or water pumped from their neighbours’ deep well. They can also do laundry at their neighbours’ place. For one batch, the neighbours get two bottles of beer as a thank you. Luckily, the barter system works here.

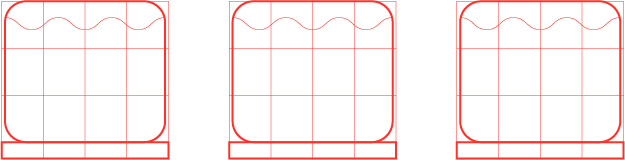

How much water does your family use in one week?

An average family of four living in a small family house connected to the water mains uses about 3,000 litres per week. That is three times the amount of water the Kopecký family from Václavice have to live on. What’s more, they don’t know when the firemen will refill their tank.

| Personal hygiene, bath, shower | 1 440 l |

| Toilet | 840 l |

| Laundry, cleaning | 140 l |

| Food preparation, dishwashing | 280 l |

| Watering | 200 l |

| Drinking | 60 l |

| Other | 40 l |

| Total | 3000 l |

The expansion of the Turów mine has already affected these municipalities. Local people have seen the level of their groundwater decrease by tens of metres. Another extension of mining does not “just” mean the loss of drinking water, as the billions spent on alternative supplies must also be taken into account.

Not even two wells will save you in Václavice. The first well provides Mr Martin only with an iron-rich liquid with high manganese content. In the second well, the water started running out 15 years ago. He deepened it at his own expense, but it still wasn’t enough. Now there is barely enough water to drink, so he has to pump service water from a well on municipal land 100 metres away twice a week.

Often not even deepening the well can solve the problem

How much time do you spend getting water?

The residents of Václavice spend up to four hours a week.

Mr Martin gets service water from a municipal well. It has become a kind of ritual for him. He stretches hoses for 100 metres and has to wait 3 or 4 hours for a 1,000-litre tank to fill. Even saving water as much as they can, his family of four uses their reserves in less than a week, or 10 days at the most. They were once so short of water that they had to fill the washing machine using a softener container.

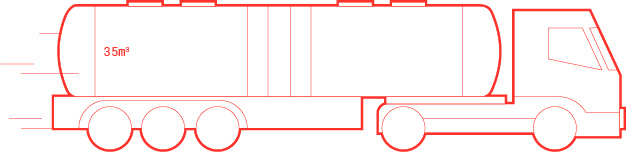

The Czech Republic is losing up to 100 water trucks of water per day.

Imagine a line of 100 water trucks. According to available studies, this is the rate of water drainage from the Czech side of the border to the Turów mine, every day. It is three times more than the people in local villages need for their everyday lives.

Mr Kirschner is affected by the water shortage mainly because of his animals. There is no water left in the 11-metre well at his farm, and a 1.5-metre natural spring there also dried up two years ago. He therefore uses a nanofiber system to filter water from the stream, providing approximately 10 litres of drinking water per hour.

An 11-metre well

has dried out completely.

He had to slaughter 6 cows.

They would have died of thirst.

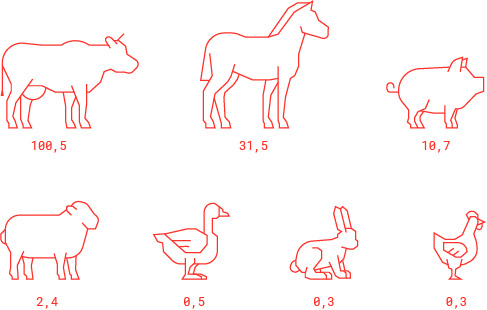

Mr Matouš also uses water from the stream for his farm animals. He has a small herd of mountain cows, as well as sheep, geese, rabbits, horses and bees. But in the spring he had to slaughter 6 of his cattle prematurely. Due to the mining and the resulting drought, the area is suffering from lack of water, which stopped new grass growing that would otherwise have replaced the hay used on his farm.

Do you know how many litres of water

farm animals need a day?

The water shortage also has other consequences. It hinders livestock production, and thus reduces the self-sufficiency and economic sustainability of affected regions.

Noise, dust and air pollution are other negative effects of the opencast brown coal mining at the Turów mine. However, the most noticeable impact is still the depletion of surface and groundwater resources.

The Gabryš family started reclamation on their land more than 13 years ago. They’ve been planting shrubs and trees to create a system that naturally retains water in the soil. This allows them to see the positive impact of their garden on local animals as well. Yet exactly the opposite trends can be seen in their surroundings: pools and streams disappearing, swamps drying out, drained fields and parched meadows.

People in Uhelná witness the devastating impacts of mining on nature.

Where a stream was flowed 13 years ago, there is now dry land.

When they look out the windows they can see Czech, Polish and German landscapes all at once. They’re watching yet another part of the woods just over the border disappear, precious soil turn into a mining area, and otherwise resilient trees in the surrounding woods die. The stream that had been flowing only a couple of hundred meters away from Uhelná when the family moved in, is slowly becoming history.

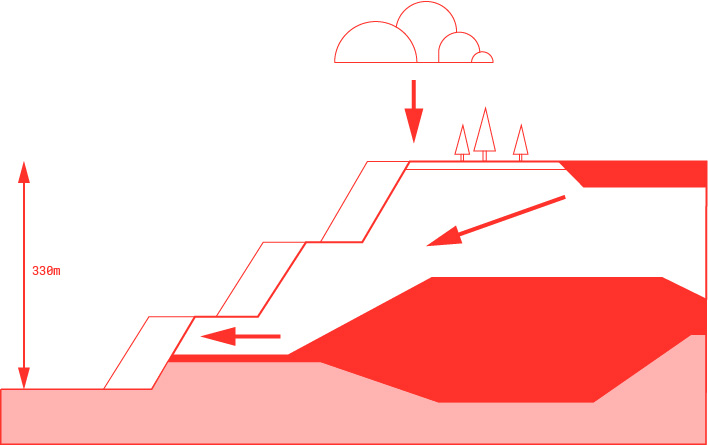

The mine’s impact on water circulation in the natural landscape

The mine’s depth and surface area are substantially affecting the surrounding ecosystem and water circulation in the natural landscape. It causes the drainage of rainwater and groundwater, and the absorption of surface water. According to current plans, the mine will be deepened up to 330 metres below ground level, equivalent to the height of the Eiffel Tower. Measurements have confirmed that the groundwater level has decreased by up to 60 metres.

Poland denies the mine’s impact on water reserves, but the families from surrounding villages know different. What will their lives look like when the mine reaches all the way to the border? And how many thousands more Czech households will face the same fate in the future?

AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE

The Liberec Region and local citizens have run out of available legal options, but their efforts to stop the expansion of the mine were unsuccessful. Poland ignored its obligations required by both European and Polish law. Moreover, the process took place without the involvement of the public or affected neighbouring states, preventing anyone expressing an opinion on the mining operation.

Poland unlawfully bypassed citizens of the Czech Republic by not allowing them to participate in the proceedings.

Bringing the case to the European Court of Justice is the last chance. Action can be taken by the EU Commission, to which the Liberec Region submitted a complaint at the end of last year. Although more than six months have passed, the European Commission has not yet initiated the necessary proceedings. But local inhabitants are running out of time. In 2023 the mining will reach within metres of the border. Until then the situation will keep getting worse.